Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

By James Laurenceson

His sobering take caused me to reflect that China-Australia relations don’t need to reach the same point but they are heading in that direction. This would be doubly disappointing because Australia leapt ahead of the US and re-established diplomatic relations with China the same year as Nixon’s visit.

There’s no clearer sign of the frosty relationship between Beijing and Canberra than the absence of a visit to China by an Australian Prime Minister since 2016. For his part, Prime Minister Scott Morrison said he is “not waiting by the phone.”

A frank appraisal would concede that an important factor behind the deterioration in China-Australia relations is a widening gap between the assessments that both countries have of their interests.

No amount of diplomatic finessing by the Australian embassy in Beijing will assuage the Chinese government’s unhappiness about the decision to exclude Huawei, a global technology leader, from participating in Australia’s 5G rollout.

And no amount of protesting by the Chinese embassy in Canberra is likely to change the Australian government’s mind that Huawei’s participation would present a national security risk that cannot be mitigated.

That said, both capitals deserve credit for allowing – for the most part – Chinese and Australian businesses and households to engage in what each sees as being of mutual benefit.

Two-way trade has never been higher, and China-Australia collaboration has extended into vital new areas such as knowledge creation. ACRI research shows that last year more Australian scientific publications included a co-author affiliated with an institution in China than any other country.

My friend and Director of the Australian Studies Centre at East China Normal University, Professor Chen Hong, is also correct in pointing out that some of the commentary about China in Australia has been inflammatory and disconnected from facts.

But what is also true, in my view, is that some of the common criticisms about Australia that are regularly made by China-based commentators, and sometimes from the Chinese government, also struggle with the facts.

And to the extent that China-Australia relations deteriorate because of misunderstandings, this is deeply regrettable.

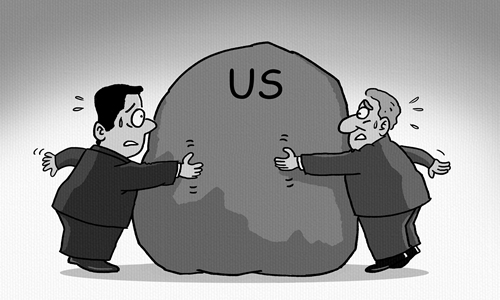

One of the most common allegations I hear is that Australia is an American lapdog.

To be sure, Australia does frequently align itself with US positions. But this is because it’s in Australia’s interests to do so. The US is Australia’s security ally and by far its most important source of foreign investment.

But this does not mean that Canberra’s support of Washington is uncritical.

In 2015, then-US President, Barack Obama, called then-Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott and asked him not to join the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. He ignored the advice and Australia joined.

I’ve lost count of the number of admirals from the United States Indo-Pacific Command in Hawaii that have come to Sydney and asked Australia to run US-style freedom of navigation patrols in the South China Sea. Each time the response has been a polite “no.”

The US has defined China as a “strategic competitor.” But on September 20, 2019, standing right next to President Trump in the Oval Office during a state visit, Prime Minister Morrison told his hosts that, “we have a comprehensive strategic partnership with China…And we have a great relationship with China. China’s growth has been great for Australia.”

Three days later in Chicago he told his American audience that “the first thing to do is acknowledge that Australia and the US come at this [the China relationship] from a different perspective.”

On issues like the need for internationally agreed to and enforceable rules on governing global trade, Australia is more closely aligned to China’s position than US’.

It is true that in the last week senior members of the Australian government have called for greater transparency from China and an independent international inquiry into COVID-19’s devastating spread. Given the death toll and rapidly rising unemployment here, many Australians would expect nothing less from their government.

But unlike in the US, Australia’s leaders have refused to label COVID-19 the “Chinese virus.”

They have also rejected President Trump’s approach of withdrawing support from the World Health Organization.

And Prime Minister Morrison has demonstrated a clear understanding of basic COVID-19 facts, telling a radio talk show host trying to stoke Australian anger toward China that “the country which has actually been responsible for a large number of these [COVID-19 infections] has actually turned out to be the United States.”

These are not the words and policies of a US lapdog.