Gods of controversy

Deep ties between Japanese politicians and religious groups have come under the spotlight once again after at least five members of Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s new cabinet were found on Wednesday to have had ties with the Unification Church.

Kishida, in quick response, reshuffled his cabinet on Wednesday as growing backlash over the ruling party’s links to the controversial religious sect saw public support plummet.

The revelations, made by cabinet members to the press, came as the revamp replaced seven ministers found to have had links with the infamous church, including former defense minister Nobuo Kishi, the younger brother of former prime minister Shinzo Abe who was shot dead last month, Japan’s National Daily reported on Wednesday.

Experts warned that politicians and extreme religious groups in some countries have formed backscratching relationships, while ordinary people who were deceived by the cults suffered.

Although the Constitution of Japan clearly stipulates the separation of religion and state, the relationship between politicians and religious corporate bodies has been ambiguous throughout Japan’s postwar political history.

Observers told the Global Times that Japanese religious bodies usually refrain from explicitly expressing support for politicians, or parties, but indirectly and implicitly support certain politicians or parties via endorsing their political thoughts or policies. Their congregants then follow suit in supporting said politicians in electoral campaigns. Some influential religious groups in Japanese politics have had a history of right-wing leanings, and have often had a strong sense of nationalism. Some of them historically were key agitators in advocating for aggression against China.

Encouraged by religious groups, Japanese leaders have repeatedly visited the Yasukuni Shrine that enshrines Japan’s infamous Class-A war criminals who symbolized Japan’s war atrocities and militarism during World War II at the risk of endangering relations with China, an open secret of collusion between politicians and religious groups.

Rising influence over Japanese politics

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida (center) visits Ise Jingu shrine in Ise, Mie Prefecture of Japan on January 4, 2022. Photo: VCG

After Japan’s defeat and surrender in the World War II in 1945, the US-led Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan carried out a series of “democratization reforms” in Japan. Article 20 of the Constitution of Japan, which was written primarily under the leadership of the US, stipulates the separation of religion and state in Japan. Coupled with that constitution’s protection of the Japanese people’s freedom of religion, religious groups sprang up in the island country after the WWII.

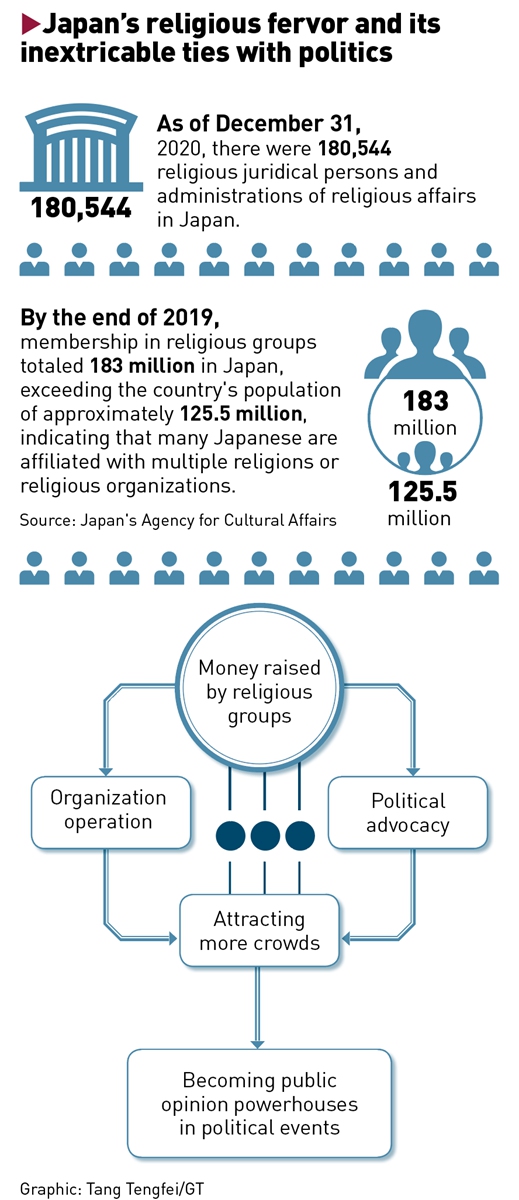

According to Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs (ACA), as of December 31, 2020, there were 180,544 religious juridical persons and administrations of religious affairs in Japan.

The number of religious people in Japan is also large. A report issued by the ACA indicates that membership in religious groups totaled 183 million as of December 31, 2019. The US Department of State estimates the total population was about 125.5 million in Japan in 2020, noting that the number of those affiliated to religious organizations in the country exceeds the country’s total population, which means that many peoole are affiliated with multiple religions or religious organizations in Japan.

The religious juridical persons and religious affairs administrations in Japan also have a strong fundraising ability. The Nippon Kaigi (known as the “Japan Conference”), Japan’s largest ultraconservative, right-wing religious group, for example, was estimated to have well over 40,000 dues-paying members as of 2020. According to the New York Times, as early as in 2014, male members had to pay 10,000 yen ($75.24) in annual fees and female members were expected to fork out half as much.

Observers point out that the earnings of religious corporations in Japan are very stable, and as long as there are no particularly unexpected major incidents, there will likely be no large scale renunciation by believers.

In general, many Japanese religious organizations, including the Nippon Kaigi, raise huge amount of money to maintain their basic operations and promote their political views, thereby attracting new members.

Whenever there is an election or an important domestic or foreign affairs event, religious followers are relied upon to become an important public opinion base.

The powerful influence of religious sects on society and politics at times encroaches on diplomatic relations between Japan and other neighboring countries.

On September 16, 2020, Abe stepped down from his role citing health reasons, but he visited the Yasukuni Shrine three days later, claiming that he had to be there to “inform the spirits of his resignation.”

Abe’s successor, Yoshihide Suga, also presented offerings at the Yasukuni Shrine on October 17, 2020. Some members of the Japanese National Diet visited the Yasukuni Shrine on the same day.

In December 2021, on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the Pacific War, a cross-party delegation of more than 100 Japanese lawmakers visited the Yasukuni Shrine collectively.

“By visiting the Yasukuni Shrine consistently, the Japanese leaders failed to consider potential damage to relations with China and offending Japan’s Asian neighbors. Behind these negative actions lies the huge influence of religion on Japanese politics,” Luo Min, a lecturer from the School of History and Culture at the Minzu University of China in Beijing, told the Global Times in a recent interview.

A collapsed Torii gate at a shrine in Minamisoma city, Fukushima prefecture on March 17, 2022 after a powerful earthquake. Photo: AFP

Typical religion-affiliated corporates behind Japanese politicians

On July 8, Abe was fatally shot while addressing a crowd at a campaign stop in Nara by a 41-year-old man identified as Tetsuya Yamagami.

Yamagami confessed to the police that he “did not resent Abe’s political beliefs,” but that his resentment toward the Unification Church, a religious movement founded in South Korea, turned into a desire to kill the former national leader.

Yamagami believed Abe had promoted a religious group to which his mother made a “huge donation,” Kyodo news agency has said, citing investigative sources. His mother subsequently went bankrupt.

The police investigation into the assassination prompted the head of the Japanese branch of the Unification Church to confirm on July 11 that Yamagami’s mother is a member.

Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has long relied on some of these powerful religious groups for both funds and electoral support. But the Unification Church is not the LDP’s chief religious backer. The larger by far is the Buddhist-based Soka Gakkai, or Value Creation Society, with a membership of 12 million congregants. The latter outfit has achieved near-ultimate political power creation. It has created a powerful political party, the Komeito, which entered into a coalition with the long-ruling LDP, according to an Asia Times report on July 14.

Officially, Komeito and Soka Gakkai are independent and separate from each other, and the Buddhist religion does not give organizational financial support to parties or their candidates, the Financial Times reported on August 3.

Soka Gakkai does, however, endorse Komeito candidates in elections and both the Komeito and the LDP have historically depended on its 7 million votes to remain in power for most of the time preceding the formation of a coalition in 1999.

“No one can match Soka Gakkai in terms of just numbers of people who go out and gather votes,” David McLellan, a professor emeritus of postgraduate Asian Studies in Tokyo who has studied Soka Gakkai for years, was quoted as saying in a Financial Times report.

For Japan’s religious corporates, having politicians, especially well-known ones, as members helps boost their influence and presence, which in turn attracts more money and members. Nippon Kaigi, known as a hub for many business tycoons and politicians who hold senior positions, is one of them, the Xinhua News Agency reported in January 2017.

Most members in Abe’s cabinet, including LDP Vice President Taro Aso and LDP policy chief Sanae Takaichi, are members of the Diet Representative Japan Conference Round-Table, which is a political wing of Nippon Kaigi. Abe’s cabinet was even called the “Japan Conference cabinet,” reflecting the huge influence of the right wing organization, said the Xinhua report.

“The vast majority of Abe’s cabinet belongs to Nippon Kaigi, an organization which is an ultranationalistic, nonparty organization with around 300,000 members who all believe in praising the Imperial Family [The Emperor], changing the pacifist constitution, promoting nationalistic education in schools, and supporting parliamentarians’ visits to Yasukuni Shrine,” McLellan told Xinhua.

It is because of the participation and support of these well-known politicians that the “Japan Conference” rapidly increased its popularity and became the largest right-wing conservative group in Japan, revealing the murky and reciprocal relationship between Japanese politicians and religious organizations.

Religious juridical persons enjoy tax-exempt treatment. Moreover, religious organizations have great capabilities, especially in collecting money, therefore, making them a convenient source of support for politicians in Japan.

Shintaro Ishihara, the former governor of Tokyo and a nationalist politician, for instance, is a member of the Reiyukai, a Japanese Buddhist new religious movement. He received a large number of votes during the elections through Reiyukai’s support, according to Xinhua.

“The prohibitions in the constitution have also made it difficult for local authorities to investigate and clamp down on controversial practices by religious groups due to fear of violating ‘religious freedom,'” said Mitsuhiro Suganuma, a former senior official at the Public Security Intelligence Agency, according to the Financial Times on August 3.

“Nobody was willing to investigate the Unification Church and its close ties with Japanese politicians because the constitution guarantees ‘freedom of religion,'” Suganuma said.

Luo, the Minzu University lecturer, said that there are various channels for Japanese religious forces to provide political donations to politicians. “The inducing behavior of some religious groups to some Japanese people has actually caused a lot of problems to Japanese society, but because of the protection of political forces, these problems have not been solved,” Luo said.

Graphic:GT

(Global Times)