It takes a little over half an hour for the flames to devour Pedro Gomes’ field at the edge of the Amazon rainforest, clearing the land for him to plant crops.

Agricultural fires like this are burning through the world’s biggest rainforest at an alarming rate, according to environmentalists using satellite data from Brazil’s space agency, INPE, to track the destruction.

But Gomes, a 48-year-old farmer with a cowboy hat and leathery brown skin, smiles as he watches his field go up in smoke.

“Can you believe the INPE’s satellites register this as a fire?” he said, as two donkeys tied up nearby watch the flames.

His blaze, he insists, is not a fire but a “queimada,” the traditional agricultural practice of clearing land by burning it during the dry season.

“How do they expect us to plant without burning?” said Gomes (not his real name).

His small 48-hectare farm is one of many burning around Novo Progresso, in northern Brazil.

The town has been shrouded in smoke for several days as farmers increased the amount of fires lit in the area.

The fuel for the fires are trees felled to clear forest for farming and ranching. Environmentalists say the fires are also fueled by the lack of consequences for those who illegally seize land and clear it.

AFP reporters traveled thousands of kilometers along roads in the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Para, where large ranches with charred trees flank the roads and newly deforested land was waiting to be burned.

In 2019, the Amazon was devastated by tens of thousands of fires that sent a thick haze of black smoke 2,500 kilometers south to Sao Paulo, causing international outcry.

President Jair Bolsonaro’s government is keen to avoid a repeat in 2020.

The far-right president took office in 2019 with calls to roll back environmental protections in the Amazon to develop mining and agriculture.

But more recently, he has tried to show he is taking action on deforestation, particularly after coming under pressure from the business sector to improve Brazil’s image on protecting the Amazon, a vital resource for curbing climate change. In July, Bolsonaro banned agricultural burning for 120 days, and has deployed the army to fight the problem.

August and September, the peak of the crisis in 2019, will be critical months to determine whether the measure has worked, as the government claims.

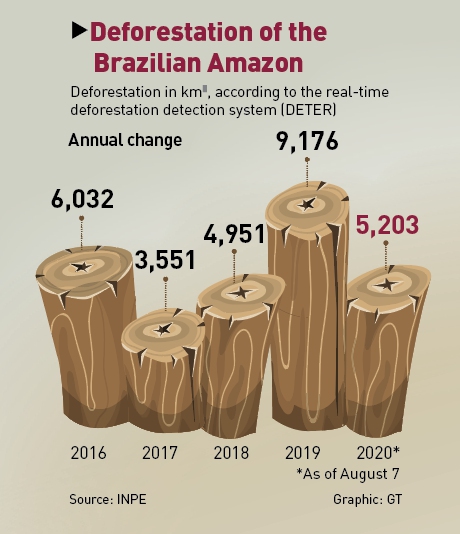

In the 12 months to July 2020, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon increased 34.5 percent year-on-year, according to INPE data.

However, the government was quick to point out that the trend improved in July, when deforestation decreased by 36 percent compared to July 2019.

‘Fire Day’

In 2019, Novo Progresso was at the center of an episode known as “Fire Day,” on August 10, when farmers allegedly burned large amounts of land in a coordinated action.

The point was purportedly to send a message to Bolsonaro: that they were holding him to his campaign rhetoric to roll back regulations protecting the Amazon.

Some dispute that account, however.

“The news media and environmental groups made that up,” says Agamenon Menezes, the president of the Novo Progresso farmers’ association. But environmentalists say fires rarely start naturally in the rainforest, because it is so wet. Many accuse Bolsonaro of encouraging people to set more blazes with his gung-ho rhetoric on developing the Amazon.

That includes on indigenous reservations and other protected land seized by squatters and speculators.

“People who seize protected lands mark their territory by razing the forest and putting cattle to pasture,” says Beto Verissimo, founder of conservation group Imazon.

“And once they cut the trees, the only way to convert the land into fields or pasture is to burn.”

Environmentalists say the budgets and staff of government agencies responsible for stopping deforestation are being gutted.

Environment Minister Ricardo Salles acknowledged in a recent interview with AFP that those agencies had a staffing shortfall of 50 percent, though he blamed the problem on previous administrations.

Exacerbating the problem, experts warn smoke from 2020’s fire season risks causing a sharp rise in respiratory emergencies at a time when Brazil is struggling to deal with the impact of COVID-19, which has killed more than 109,800 people in the country as of Wednesday.