By Hu Yuwei, Huang Ge and Peng Zefeng in Kathmandu

○ Bribery and graft are rife among officials in Dharamsala, according to a disillusioned former employee

○ Many ethnic Tibetans eager to return to China after learning of economic progress in their homeland

○ Separatists losing clout as most young Tibetans focus on finding ways to make ends meet

After working for the Tibetan “government-in-exile” for eight years, Tashi Tsering (pseudonym) finally decided to quit and return to Nepal from India.

The ethnic Tibetan, in his 40s, is now living in Nepal as a refugee.

“It felt like a world of lies and false hopes,” he concluded of his eight years of propaganda work for the Tibetan “government-in-exile” in Dharamsala, India.

Tashi Tsering is one of more than 20,000 ethnic Tibetans living in Nepal who have moved across the Himalayas from their hometowns in Tibet since 1959. He left Lhasa in 1990, trekking over 6,000 kilometers for four days to cross the treacherous Himalayas, paying a smuggler 500 yuan ($104.50 at the 1990 rate), to reach Nepal before being sent to India.

“There was no hot food at all, and I quenched my thirst with snow,” he recalled of his difficult journey, saying that he pinned all his hopes on the “pure and tranquil world of bliss” over the mountains.

He was sent to India one week later, and in 1997 was offered a position in the propaganda department of the Tibetan “government-in-exile” because of his talents. He still remembered how “grateful and honored” he felt to be blessed by the 14th Dalai Lama in their first meeting.

But that feeling of glory quickly faded.

Open secret

“Officials within the ‘government-in-exile’ come from very mixed backgrounds. Many who claimed to be political refugees asking for positions were actually street scoundrels or even criminal thugs in Tibet. The ‘government-in-exile’ is not always clear about the real situation in Tibet, and often speculates subjectively about the autonomous region,” Tashi Tsering told the Global Times.

Even worse than the disorganized structure and system was the cronyism and corruption, which constantly baffled Tashi Tsering, who speaks of deceptive accounting for external aid and constant bribery.

“The problems are open secrets among officials, but anyone who dares to speak about them may be quickly accused of being a ‘spy of the Chinese government’ and then immediately expelled,” he said.

“They also make up facts about what is happening in Tibet, always giving unwarranted blame to the Chinese government,” he said.

The lies and crimes finally made Tashi Tsering decide to quit and return to Kathmandu from India.

“They never care about the real interests of the exiled Tibetans. We are more like chips used to immigrate to the West,” said Tashi Tsering, convinced that there was no longer any point in staying in such a corrupt agency.

After returning to Nepal, Tashi Tsering chose to teach Chinese in a Buddhist school for the following five years. The desire to go back to China was a clear trend among Tibetans exiled in Nepal, he said, which was made evident by the large drop in students leaving Tibet in recent years. He believes that the school will be closed in the near future.

“Almost everyone around me wants to go back, but it is too hard,” he said.

Eager to return

Almost every Tibetan the Global Times has interviewed had a common response: they were “eager to go back.”

Every week, ethnic Tibetans line up to apply for a return-to-Tibet permit at the consulate office of the Chinese Embassy in Nepal, but the number of places granted has been shrinking since 2008. An office worker told the Global Times that Tibetans applying for a permit need to go through a background check on their past activities and family connections in their hometowns.

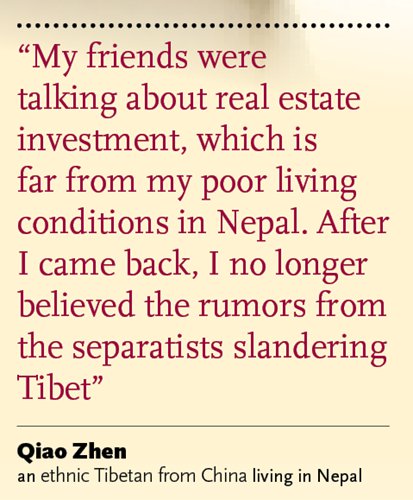

Qiao Zhen has submitted an application for the third time. She went back to Tibet once with a permit in 2014, and was impressed by the sweeping changes in the autonomous region.

“My friends were talking about real estate investment, which is far from my poor living conditions in Nepal. After I came back, I no longer believed the rumors from the separatists slandering Tibet,” she told the Global Times.

Most Tibetans living in Nepal have limited access to rights and services, as they have neither Nepalese citizenship nor a Refugee Identity Card which is issued by the Indian government to Tibetans seeking asylum.

Their right to work is particularly restricted; many employers are unable to hire them even though Tibetan employees are cheaper, said one Nepalese restaurant owner. Most exiled Tibetans like Qiao Zhen rely on niche enterprises in tourism or selling Tibetan souvenirs.

“Without any identification, I have no idea where I belong. I have been living here for 10 years, but it’s not my home. There is no future for an elderly woman here,” Yangkey, a 69-year-old Tibetan refugee, told the Global Times in the Tibetan settlement of Pokhara, Nepal’s second largest city.

Qiao Zhen said that she left Tibet in her 20s because of her love of Indian films, which portrayed India as a paradise. Exiled Tibetans revealed that their reasons for leaving Tibet varied greatly. These include studying Buddhism and learning English in India, or going to see the 14th Dalai Lama, quite apart from the so-called political persecution widely claimed by Western media.

Tashi Tsering complained that many young Tibetan students in Nepal are struggling to find local jobs, even those who hold a master’s degree.

“I never heard of any Tibetan girls selling sex here for a living in the early 1990s, but now I sadly heard it happens,” he said.

Tashi Tsering has a Nepalese wife, but is still not entitled to a Nepalese identity. Tibetan women can get that status if they marry a Nepalese man, but the reverse is not applicable, according to local law.

But even having an official identity does not ease their hardship. Jigme Norbu came to Nepal in 1999. He obtained a Nepalese citizenship, but it is still hard for him, a migrant worker, to provide a good education for his children, as they cannot enjoy any preferential education policy treatment in Nepal, unlike those in Tibet who have educational preferential policies provided by the Chinese central government.

Tashi Tsering said that the “government-in-exile” has not given him any substantial support during his 10 years in Nepal, apart from 320 rupee ($2.88) during the earthquake in Nepal in 2015.

Impressed by changes

Most Tibetans in Nepal hear about the development taking place in Tibet from their relatives, but Nepalese media has contributed more to their understanding of the situation, especially in recent years. The 24-hour Tibetan-language channel launched by The Tibet Television Station in Nepal offers a broader understanding of the region. The China’s Tibet Bookstore, located in Kathmandu and opened in December 2009, also helps spread knowledge.

Zhang Jun, the bookstore’s director, told the Global Times that more than 70 percent of the visitors to his bookstore are monks. The bookstore now has nearly 20,000 books in Tibetan, English and other languages, as well as a small number of books in Chinese.

It not only builds a bridge that allows Nepalese people to know China better, but also plays an important role for exiled Tibetans in understanding the new face of Tibet since the reform and opening-up, he said.

The bookstore holds thematic art exhibitions or presents documentaries about Tibet on important anniversaries. Some of the older customers cry when they see pictures of their hometowns.

But Zhang said the attempts of Tibetans in Nepal to get closer to Tibet are sometimes obstructed and undermined by local separatists.

During an exhibition in 2011, a Tibetan girl who was invited to participate suddenly stopped when she reached the door.

“She said she was afraid that she might be spied on by separatists in secret and her life might be affected if she stepped in,” Zhang told the Global Times. It was not the first time he had come across such a situation.

Separatism weakened

There are at least 11 Tibetan settlements across Nepal, with an estimated 15,000 long-term resident Tibetans living in Kathmandu. Others live quietly in remote villages scattered across the mountains.

Signs of pro-separatist movements or inflammatory posters are not visible. The pro-separatists seem to have lost their clout while the Tibet Autonomous Region in Northwest China has been making steady improvement both economically and politically.

The Tibetan communities in Nepal are aging, while younger Tibetans are leaving to seek better employment opportunities elsewhere.

“Nobody is interested in pro-separatist activities. They care more about survival here,” said Qiao Zhen.

“Tibetans in Nepal have become less dependent on Western groups nowadays. In the past, those who joined separatist activities could secure a chance for immigration, but now they don’t count on it,” said Zhang Ming, a professor at the Faculty of Social Development and Western China Development Studies, Sichuan University.

“They know the West sees them only as a political card,” he said.

Source:Global Times