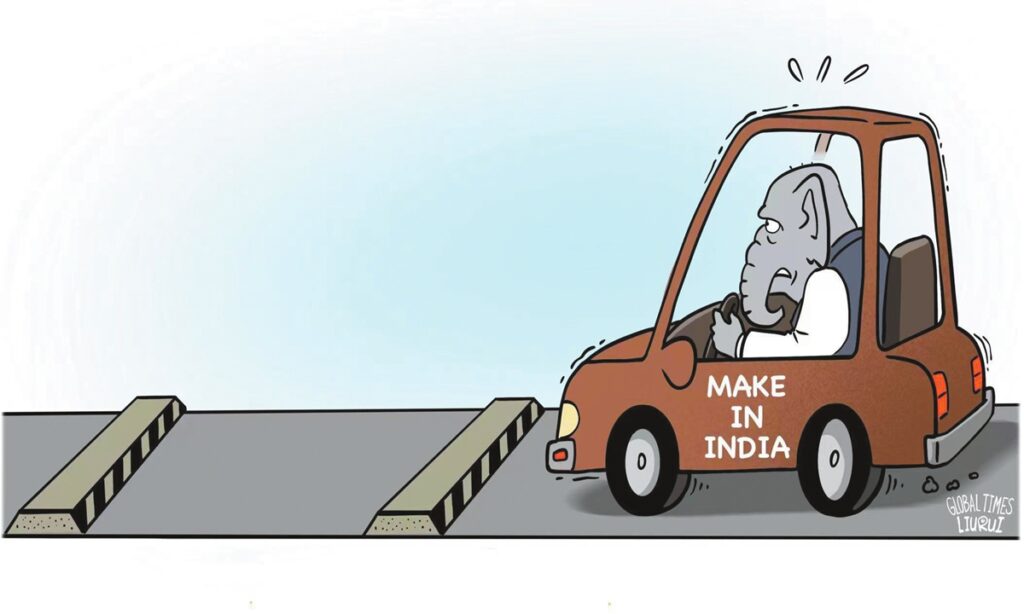

Four years after launching its $23 billion Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme aimed at challenging China’s manufacturing dominance, India’s flagship “Make in India” initiative has become a cautionary example of institutional inertia. As revealed by Reuters on Friday, this once highly anticipated and ambitious program has veered off course.

According to World Bank data, manufacturing accounts for only around 13 percent of India’s GDP – far lower than China’s 26 percent and Vietnam’s 24 percent. Although this is 2023 data, it is clearly impossible to increase India’s manufacturing sector to 25 percent of GDP by 2025 as envisaged by Prime Minister Modi.

These figures reflect a deeper systemic malaise. The reality of India’s manufacturing development demonstrates that the human factor remains decisive, requiring a departure from colonial institutions and ideological frameworks. This constitutes not merely institutional adjustment and innovation, but more profoundly, a protracted revolution in thought. Foreign investors consistently report that these structural barriers severely constrain workforce development, caste system reform and administrative efficiency – key ingredients for a manufacturing takeoff.

India’s reform efforts resemble colonial-era patchwork – superficial adjustments that preserve a bureaucracy originally designed to serve imperial extraction rather than foster modern industrial governance. At its core, this system serves the ruling elite rather than cultivating a modern workforce. Colonial governance structures, designed for control rather than development, continue to suffocate India’s innovation capacity and policy execution. India’s reform efforts on education and caste discrimination remain headwinds for industrial growth.

India’s challenges extend beyond regulatory complexity or policy bottlenecks. Colonial-era land laws, convoluted approval processes and an inefficient judiciary continue to suppress investment and innovation. The fragmented governance model, with regions operating in silos, has created disparities and operational chaos at the local level, leaving manufacturing hubs starved of the cohesive and agile policy support they critically require.

The stagnation of India’s education system further highlights the problem of colonial institutional legacy. In a joint study, Nitin Kumar Bharti, Postdoctoral Fellow at New York University Abu Dhabi, and Li Yang, Research Fellow at the Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research, argue that the core reason for India’s manufacturing lag lies in its education system’s historical path dependency. They point out that the education model formed during British colonial rule resulted in India’s long-standing emphasis on higher education over basic education, and a preference for humanities disciplines over STEM subjects.

The path forward lies in systemic institutional reform that suits India’s realities. To join the ranks of manufacturing powers, India must shed the shackles of its colonial inheritance: streamline governance structures, advance local empowerment and foster an industrial workforce through educational equality. This requires moving beyond the PLI scheme’s “financial band-aid” approach toward a comprehensive alignment between the machinery of the state and the demands of modern industry.

For developing nations, this divergence offers a critical lesson: successful industrialization requires institutional reconstruction, not mere imitation. Breaking free from colonial legacies and Western frameworks, as well as building institutions tailored to national conditions, can unlock transformative potential.

As global supply chains rapidly evolve, the window for reform is narrowing. India’s future depends not on copying others but on rewriting its economic operating system. This serves as both an important lesson for developing nations and a compelling validation of following a development path rooted in national context. GT