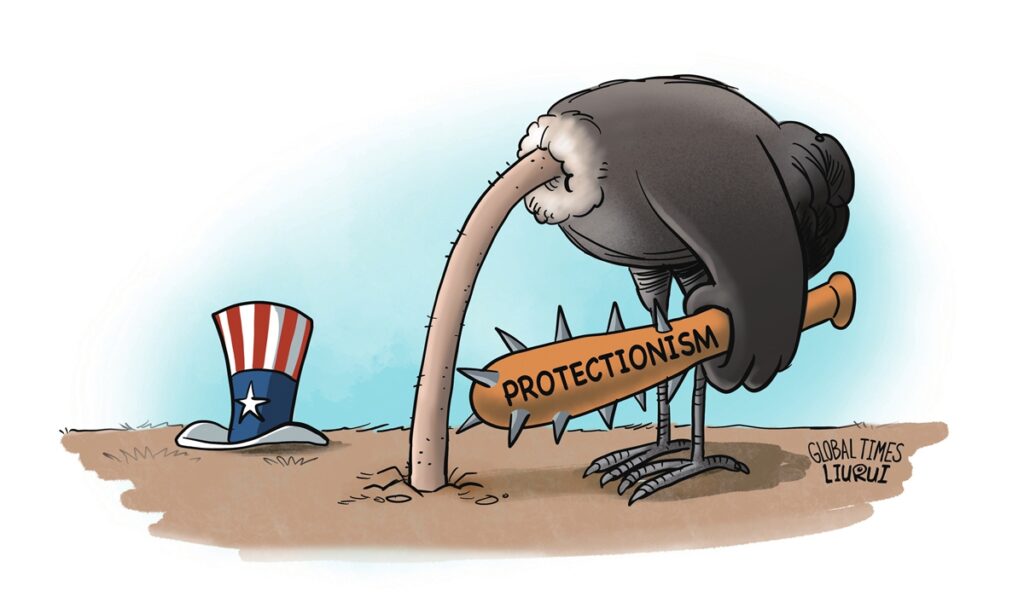

Microsoft President Brad Smith recently warned that underestimating China’s technological progress is “dangerous.” The crisis awareness he expressed is understandable – any successful entrepreneur would seek to maintain an absolute lead in a competition. However, he overlooks the real “danger”: this sense of crisis in the US has been turning into trade protectionism and tech blockades, replacing healthy open competition.

On Tuesday, Smith told CNBC that in many ways, China is close to or is even catching up on technology. “I think one of the dangers, frankly, is that people who don’t go to China too often assume that they’re behind,” he said.

A contradiction is evident here – while the US keeps amplifying China’s technological progress as a “threat,” how can someone still assume that China’s technology is “behind”?

Lü Xiang, a research fellow at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times that an unspoken context is that the US has repeatedly smeared China by accusing it of “stealing intellectual property,” covering up China’s arduous efforts in the tech field, leading many to view China’s technological achievements as “stolen.”

Yet, the ongoing tech war initiated by the US itself proves that such claims are baseless.

Over the past years, the US government has spared no effort in curbing China’s high-tech industry through approaches like export restrictions, and sanctions.

Yet amid escalating tech blockades, China has made rapid breakthroughs in chip technology, built the world’s largest 5G network with the most advanced technologies, and the power battery technologies independently developed by companies such as BYD and CATL are leading the world.

The ongoing Airshow China in Zhuhai, South China’s Guangdong Province, also demonstrates China’s progress in developing domestically produced aircraft engines, with stealth fighters like the J-20 and J-35 powering their “hearts” with homegrown engines.

What Smith is trying to remind people of is this – don’t assume that China lacks technological innovation, Lü said.

If the current China-US competition was healthy, his reminder would be perfectly reasonable.

However, the US has forgotten what healthy competition truly looks like. China, on the other hand, has plenty of examples.

For instance, Tesla’s first factory outside the US is in China, with China allowing Tesla to wholly own its operations.

It sparked a “catfish effect,” energizing Chinese electric vehicle companies and stimulating the rise of the entire Chinese EV industry.

The problem is that the sense of crisis, as expressed by Smith, has not been channeled into motivating the US to engage in healthy competition. Instead, it has only intensified the tech war.

What most American elites feel about China is no longer just a sense of crisis, but paranoia – the more technological progress China makes, the more “dangerous” it is perceived to be.

However, blocking China’s progress cannot restore the US’ own advantage, and tech wars won’t halt China’s advancement.

The US’ containment efforts against Huawei did not prevent the company from building the world’s largest 5G network or becoming a leader in global 5G technology.

Meanwhile, analyses suggest that the US is losing the 5G race.

The US’ sense of crisis cannot be alleviated through a tech war, as the facts have shown it to be a wrong path.

Instead, it should confront the decline in its own innovation capacity, reflect on why a once-global tech empire is now facing innovation bottlenecks, and explore how it can revive its former creativity and vitality.

Most importantly, it must acknowledge this truth: suppressing others will never lead to progress.

GT