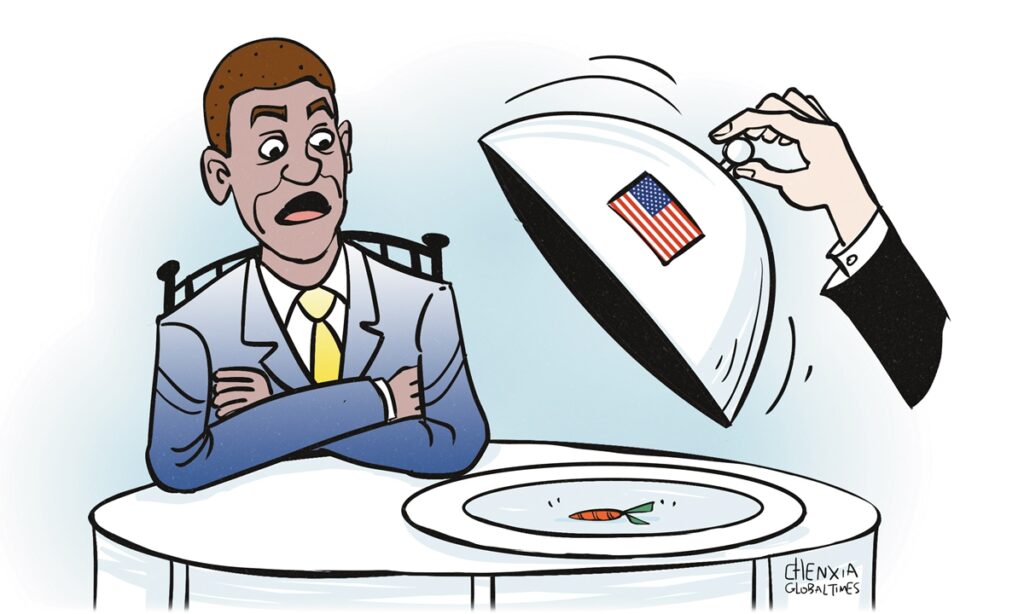

“The United States is all in on Africa and all in with Africa” was a slogan declared back in 2022. How exactly is the US all in on Africa? Now we have the answer: just as US president is about to leave office, he finally remembers to visit the continent. But wait, the visit is being postponed again.

President Joe Biden has put off his overseas trip this week due to Hurricane Milton, the White House announced on Tuesday local time without mentioning a new date for the trip. He was previously scheduled to make his first visit to Africa during his presidency in Luanda, the capital of Angola, located on the west-central coast of southern Africa, from October 13 to 15.

Some Western media have characterized this visit as fulfilling an earlier promise – Biden’s commitment to visit Africa in 2023 made at the US-Africa Leaders Summit in 2022. However, this promise has not been genuinely realized. Although figures such as Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and even US First Lady Jill Biden visited Africa last year, the president himself did not set foot on the continent in 2023. Clearly, the fulfillment of this promise will have to wait even longer now. Furthermore, when the US is mentioned, Africans are concerned about whether American policies toward Africa will remain consistent over time.

The turnover of political parties in the US creates inconsistencies in government policies. More importantly, there has always been a disconnect between US policies and Africa’s actual needs. African countries wish to achieve their own development. Yet US strategy toward Africa has largely been a stress response, Shen Yi, a professor at Fudan University, told the Global Times.

Shen explained that when the Soviet Union cooperated with Africa, the US competed for dominance. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the US gradually withdrew from the continent, showing little interest in supporting sustainable development there. Now, with China’s rise and the rapid increase in cooperation between China and Africa, the US has become increasingly concerned about China’s growing influence and status on the continent, prompting it to turn its attention back to Africa, seeking ways to counter China. In this process, the US has often played the role of disruptor in Africa rather than a constructive partner.

In recent years, the US has tried hard to use infrastructure as a tool to engage in major power competition in Africa. For example, in 2023, the US and its European allies launched the Lobito Corridor project, a railway project stretching from the Angolan port of Lobito on Africa’s Atlantic coast to the city of Kolwezi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The US hails it as “the largest US infrastructure investment in Africa ever,” and proudly announced that itself and its partners have committed over $4 billion to Lobito Corridor projects, with Washington now funding $250 million.

Ironically, Nigerian journalist David Hundeyin pointed out that a simple glance at the map of the railway tells a clear and unmistakable story about the purpose and intentions behind the Lobito Corridor, evacuating resources quicker and with less local participation. The route of the railway, almost entirely devoid of any kind of meaningful interaction with African industrial or population centers, shows an obvious aim to transport Congolese minerals from mine to port as quickly as possible.

The author also pointed out that when the West is busy building colonial-style railways from mine to port, China-invested Huatong Aluminum Industrial Park is taking shape, with the aim of creating an Aluminum industry chain in Angola. The differences between Chinese and US investment are strikingly apparent.

Through the upcoming visit, the Biden administration primarily focuses on shaping its diplomatic legacy while attempting to improve its connection with African American voters. The African tour won’t change the true nature of US policy toward Africa – a variant of a colonial strategy, Shen said.

It is difficult to even name a US project in Africa that can really be called mutually beneficial. Even setting projects aside, the superficial diplomatic gestures speak for themselves. During the US-Africa Leaders Summit two years ago, some African leaders complained about “crossing the ocean to come [to Washington]” only to be “loaded into buses like school kids” as the gathering lacked one-on-one meetings between US president and African heads of state. If the US genuinely valued Africa, it would prioritize a visit to the continent within the first year of a new administration.

Ultimately, the US strategy toward Africa is driven by anxiety over competition with China. As long as China focuses on solidifying mutually beneficial cooperation with Africa, US anxiety won’t change anything.

GT