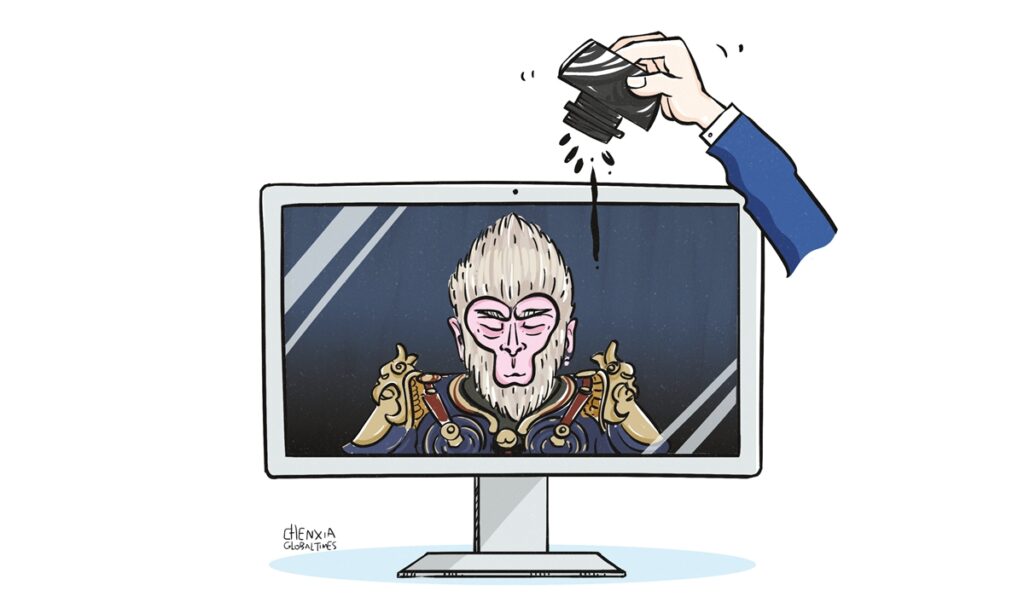

Black Myth: Wukong, a video game that embodies the dream of Chinese gamers to have a game deeply rooted in Chinese culture and on par with the best games globally, has been a major hit since its debut. However, just like every success China has had, Western media’s criticism is never far behind.

Even if Western media can’t deny the game’s global success, there is often a classic “but” in their reports. “‘Black Myth: Wukong’ Is a Hit. But Why Is the Game So Controversial?” US magazine Rolling Stone asked recently, stressing that the game lacks “inclusivity and diversity.” A BBC headline was entirely negative: “Blockbuster Chinese video game tried to police players – and divided the internet.”

The criticism about inclusivity and diversity appears to be a rushed judgment from journalists or commentator who spent only a few hours with the game. If they played longer, they would see that female characters do appear over time. The point it, true players don’t really care about it. As some overseas netizens put it – it’s a game, not a movie, it doesn’t need to cater to Western political correctness by including diverse female characters or transgender individuals.

The recent attacks from some Western media outlets come after Black Myth: Wukong has challenged the gaming ecosystem in the Western world, Shen Yi, a professor at Fudan University, told the Global Times. In this system, consulting firms like Sweet Baby Inc offer costly diversity, equity, and inclusion advice for video games. Black Myth: Wukong, however, not only reportedly showed no interest to obediently conform to distorted rules but also achieved unprecedented success. This has sparked both envy and fear among those who control the ecosystem and led to the recent attacks focused on gender, diversity, and inclusivity.

Moreover, the radar of some anti-China forces is triggered when Black Myth: Wukong is increasingly considered as a symbol of China’s soft power, prompting foreign players to rediscover China’s capabilities while promoting the global spread of traditional Chinese culture. The BBC – which cannot accept the fact that China’s image is improving through the game – wrongly accuses China of censorship to dampen international perceptions of China.

Their strategy of attacking the game is just the same old Western tactic – politicizing every Chinese achievement, even in the realm of gaming. What’s next? Will they portray the Chinese gaming industry as a “threat” in the future?

What they fail to grasp is that whether players choose to pay for a game is never about ideology, or political correctness over diversity. The game’s quality is what truly matters. Feng Ji, founder of the game’s developer Game Science, recently said that cultural export was not the initial goal of the game. Yet he believes that if the quality is high enough, it will naturally radiate to the overseas market.

He made it. Black Myth: Wukong’s high quality has fueled its popularity. Many international players enjoy the game, which has inspired their curiosity about Journey to the West and Chinese culture.

If Black Myth: Wukong hadn’t been successful, if it hadn’t topped sales charts worldwide, and if it had been just an average game, would Western media even care about it? They would probably just claim that China has no AAA game. The fact that they attack the game proves its success and highlights the persistent cultural hegemony and arrogance of some in the West. While Chinese people have long been opening up to the world, some Westerners are still unwilling to recognize China as it is.

GT